The domestication of plants and animals, as well as the creation and diffusion of techniques for raising them effectively, are all documented in the history of agriculture. Agriculture began separately in several places of the world, and it encompassed a wide variety of species. As autonomous origin centers, at least eleven different locations of the Old and New World were involved.

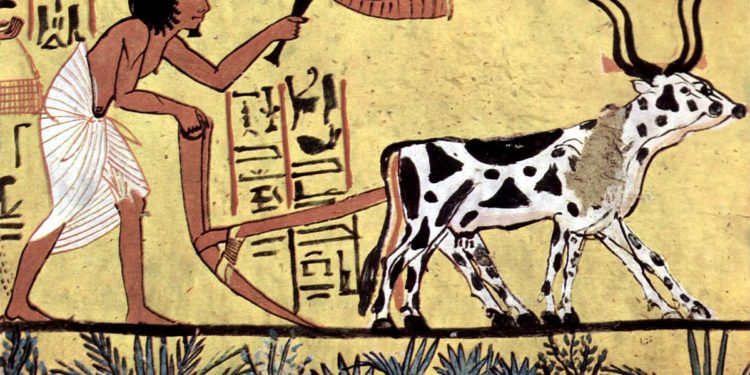

Ancient agriculture

Wild grains have been harvested and consumed since at least 105,000 years ago. Domestication, on the other hand, did not occur until much later. The eight Neolithic founder crops — emmer wheat, einkorn wheat, hulled barley, peas, lentils, bitter vetch, chickpeas, and flax – have been produced in the Levant since circa 9500 BC.

Although rye may have been cultivated earlier, this assertion is debatable. Rice, mung, soy, and azuki beans were all cultivated in China by 6200 BC, with the earliest known cultivation dating back to 5700 BC. Pigs were domesticated circa 11,000 BC in Mesopotamia, and sheep were domesticated between 11,000 BC and 9000 BC. Around 8500 BC, cattle were domesticated from wild aurochs in modern-day Turkey and India. By 3000 BC, sorghum had been domesticated in Africa’s Sahel region. Camels were domesticated relatively late in history, perhaps around 3000 BC.

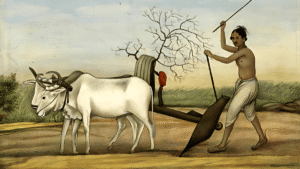

Agriculture was intensified in Mesopotamian Sumer, ancient Egypt, the Indus Valley Civilization of the Indian subcontinent, ancient China, and ancient Greece during the Bronze Age, which lasted from 3300 BC to 3300 BC. The expansion of ancient Rome, both the Republic and then the Empire, throughout the ancient Mediterranean and Western Europe during the Iron Age and era of classical antiquity built on existing agricultural systems while also establishing the manorial system, which became the bedrock of medieval agriculture.

Agriculture was altered during the Middle Ages, both in Europe and in the Islamic world, by improved techniques and the spread of crop plants, including the introduction of sugar, rice, cotton, and fruit trees such as the orange to Europe via Al-Andalus. The Columbian exchange introduced New World foods such as maize, potatoes, tomatoes, sweet potatoes, and manioc to Europe after Christopher Columbus’ expeditions in 1492.

Around 7000 BC, New Guineans cultivated sugarcane and several root crops. In Papua New Guinea, bananas were farmed and hybridized at the same time. Agriculture was first practiced in Australia at an indeterminate time, with the oldest eel traps of Budj Bim going back to 6,600 BC and the planting of a variety of crops ranging from yams to bananas.

Agriculture in prehistoric South America

Agriculture began in South America as early as 9000 BCE, with the cultivation of a few types of plants that ultimately became minor crops. Potatoes, along with beans, tomatoes, peanuts, coca, llamas, alpacas, and guinea pigs, were domesticated in the Andes of South America between 8000 BC and 5000 BC. Cassava was cultivated as early as 7000 BC in the Amazon Basin.

Maize (Zea mays) originated in Mesoamerica, where wild teosinte was tamed and genetically altered to become domestic maize around 7000 BC. Cotton was domesticated in Peru by 4200 BC, and another species was domesticated in Mesoamerica, where it became the most significant cotton species in the textile industry in contemporary times.

Changes in agricultural activity as a result of colonization

Irrigation, crop rotation, and fertilizers were introduced shortly after the Neolithic Revolution and have progressed significantly over the last 200 years, beginning with the British Agricultural Revolution. Agriculture has seen huge increases in productivity in the developed world, and to a lesser extent in the developing world, since 1900, as human labor has been replaced by technology, which has been aided by synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, and selective breeding.

The Haber-Bosch process enabled the industrial production of ammonium nitrate fertilizer, which considerably increased crop yields. Overpopulation, water pollution, biofuels, genetically modified organisms, tariffs, and farm subsidies are just a few of the social, political, and environmental challenges that modern agriculture has brought up. As a result, organic farming emerged in the twentieth century as a viable alternative to petrochemical pesticides.

Early development in agricultural farming

Early humans began modifying flora and fauna populations for their personal profit through methods such as fire-stick farming and forest gardening. From at least 105,000 years ago, and maybe much longer, wild grains have been harvested and eaten. Because people collected and ate seeds before domesticating them, exact dates are difficult to verify, and plant features may have altered over this time without human selection.

The semi-tough rachis and bigger seeds of cereals from the early Holocene in the Fertile Crescent’s Levant region, for example, date from just after the Younger Dryas (about 9500 BC). Without any human influence, monophyletic traits were achieved, showing that apparent domestication of the cereal rachis could have occurred spontaneously.

Agriculture began separately in several places of the world, and it encompassed a wide variety of species. As autonomous origin centers, at least 11 different locations of the Old and New World were involved. Animals were among the first domesticated species. Domestic pigs originated in Eurasia, specifically in Europe, East Asia, and Southwest Asia, where wild hogs were first domesticated some 10,500 years ago. Between 11,000 and 9000 BC, sheep were domesticated in Mesopotamia. Around 8500 BC, cattle were domesticated from wild aurochs in modern-day Turkey and Pakistan. Camels were domesticated relatively late in history, perhaps around 3000 BC.

The eight so-called founding crops of agriculture did not develop until after 9500 BC: first, emmer and einkorn wheat, then hulled barley, peas, lentils, bitter vetch, chickpeas, and flax. These eight crops appear on Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) sites in the Levant almost simultaneously, though wheat was the first to be produced and harvested on a large scale. Parthenocarpic trees were cultivated around the same time (9400 BC).

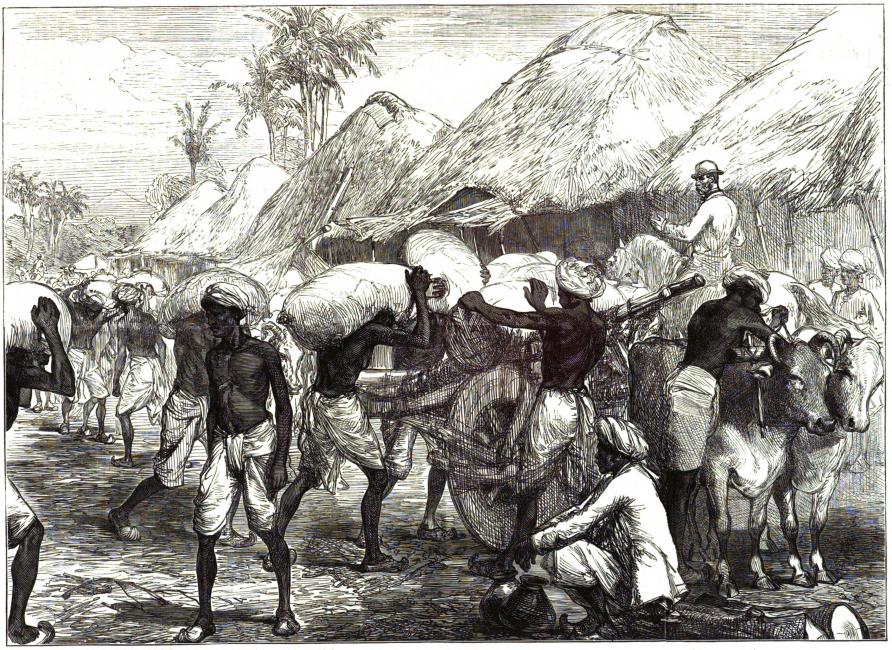

Agricultural activities during the middle ages all over the world

From 100 BC to 1600 AD, the global population and land use continued to grow in lockstep, as indicated by the rapid rise in methane emissions from livestock and rice agriculture. Agriculture improved even more during the Middle Ages. Monasteries sprang up all over Europe, and they became important repositories of agricultural and forestry knowledge. The manorial system gave big landowners control over their property and workforce, who were either peasants or serfs.

During the Middle Ages, the Arab world played a crucial role in the flow of crops and technologies between Europe, Asia, and Africa. They introduced the notion of summer irrigation to Europe and built the beginnings of the sugarcane plantation system through the employment of slaves for intensive cultivation, in addition to transporting a variety of crops.

Modern agriculture

Between the 17th and the mid-nineteenth centuries, agricultural production and net output in Britain skyrocketed. Enclosure, mechanization, four-field crop rotation to retain soil nutrients, and selective breeding enabled a tremendous population increase to 5.7 million in 1750, freeing up a substantial portion of the labor and so helping to drive the Industrial Revolution.

The biggest issue in sustaining agriculture in one location for an extended period of time was the depletion of nutrients in the soil, particularly nitrogen levels. To allow the soil to rejuvenate, fertile land was frequently left fallow, and crop rotation was adopted in some cases. In the 18th century, British agriculturist Charles Townshend popularized the Dutch four-field rotation system. Wheat, turnips, barley, and clover were used to create a fodder and grazing crop, allowing livestock to be bred all year. Clover was particularly useful because the legume roots supplied soil nitrates.

The arrival of new technical equipment during the 20th century

In 1901, the International Harvester Farmall tractor became the first commercially successful gasoline-powered general-purpose tractor, and in 1923, the International Harvester Farmall tractor represented a turning point in the replacement of draught animals (especially horses) with machines. Agriculture has been further revolutionized by the development of self-propelled mechanical harvesters (combines), planters, Transplanters, and other equipment since that time. These innovations allowed farmers to complete chores at a pace and scale never before imaginable, allowing modern farms to produce significantly higher volumes of high-quality produce per acre of land.

Agriculture has been marked by improved productivity, the use of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides in place of labor, water contamination, and farm subsidies over the last century. Gene modification, hydroponics, and the development of economically viable biofuels such as ethanol are some of the other applications of scientific study in agriculture since 1950.

Famines, on the other hand, continued to ravage the world throughout the twentieth century. Millions of people died in at least 10 famines between the 1920s and the 1990s as a result of weather occurrences, government policy, conflict, and crop failure.

Finally, the green revolution steps in-

Between the 1940s and the late 1970s, the Green Revolution was a series of research, development, and technology transfer programs. It boosted agricultural production all across the world, particularly after the late 1960s. The initiatives, led by Norman Borlaug and credited with saving over a billion people from starvation, included the development of high-yielding cereal grain varieties, expansion of irrigation infrastructure, modernization of management techniques, distribution of hybridized seeds, synthetic fertilizers, and pesticides to farmers, and distribution of hybridized seeds, synthetic fertilizers, and pesticides to farmers.

In the early twentieth century, synthetic nitrogen, combined with mined rock phosphate, herbicides, and mechanization, dramatically enhanced crop yields. Increased grain supplies have also resulted in cheaper livestock. Furthermore, later in the twentieth century, when high-yield varieties of common staple grains like rice, wheat, and corn were developed as part of the Green Revolution, worldwide yields increased.

The Green Revolution brought developed-world technologies (such as pesticides and synthetic nitrogen) to the developing world. Thomas Malthus, a well-known economist, famously prophesied that the Earth’s population would outstrip its ability to maintain it, yet advances like the Green Revolution have allowed the globe to create a surplus of food.

Although the Green Revolution first raised rice yields in Asia, they eventually plateaued. Wheat’s genetic “yield potential” has risen, but rice’s yield potential has remained unchanged since 1966, and maize’s yield potential has “barely increased in 35 years.” Herbicide-resistant weeds emerge in a decade or two, and insecticide-resistant insects emerge in approximately a decade, albeit with some delay due to crop rotation.

Also Read: How The Emerging Agritech Startups Are Empowering Farmers.